In an April 2024 piece published in Project Syndicate, Dani Rodrik addresses this question. My posting, based on Rodrik’s article, adds information to support the following primary claim that Rodrik makes:

It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that boosting manufacturing employment is like chasing a fast-receding target. The world has moved on, and the nature of manufacturing technologies has changed irrevocably. Automation and skill-biased technology have made it extremely unlikely that manufacturing can become the labor-absorbing activity that it once was. Whether we like it or not, services such as retail, care work, and other personal services will remain the primary engine of job creation. That means we need different types of good-jobs policies, with a greater focus on fostering productivity and labor-friendly innovation for services.

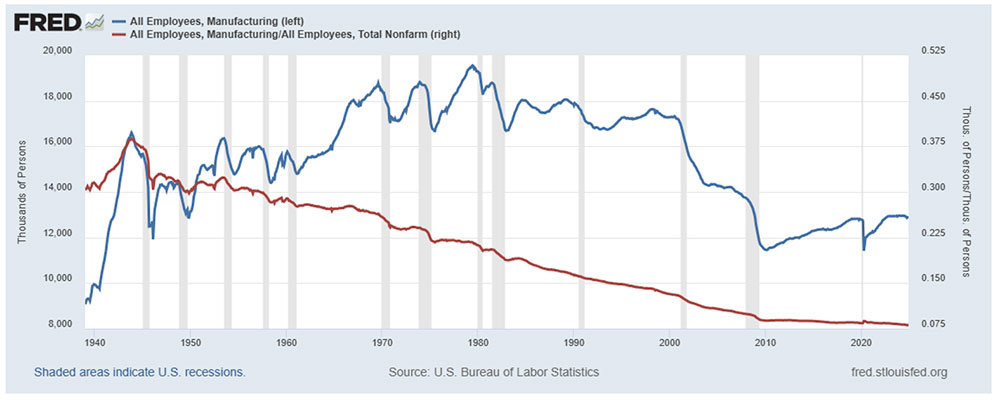

The below chart illustrates for the U.S. the decline in the level of employment in manufacturing since 1979.

When manufacturing employment was at its peak in 1979, it constituted 21.5% of non-farm employment in the U.S. By 2000, manufacturing’s employment share had fallen to 13.1%, and it has continued to fall to 8.1% in 2020 before the Covid-pandemic, where it remains in the most recent data provided by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

One primary macroeconomic policy goal in the U.S. has been to create “good jobs”, that is, well paid jobs that sustain employment for a sizeable portion of the civilian labor force. Production and non-supervisory employees in manufacturing used to provide such. Now, the median wage for these workers has fallen below the median wage for all such employees. Based on data provided by FRED, the St. Louis Federal Reserve’s database, in 2000, at $14.30 per hour the wage rate in manufacturing was just 1% above the national median for such production workers. By 2010, at $18.57, it had fallen to 2% below the national average, and the most recent rate (May 2024), at $27.79 per hour, falls below the national average for such workers by almost 8%.

The decline in manufacturing as a share of employment is not unique to the US. As shown in the following table, the share of employment in manufacturing has fallen precipitously in many high income countries since 2000.

| Country | 2000 | 2022 (or most recent) |

| USA | 13.0% | 9.9% |

| Japan | 20.6% | 15.5% |

| Germany | 23.8% | 19.9% |

| France | 18.8% | 11.0% |

| United Kingdom | 16.9% | 9.1% |

| Netherlands | 13.9% | 8.3% |

Lower valued manufacturing has shifted to countries that have a labor force sufficiently skilled to deliver such goods at a much lower cost than can be provided in high income countries. More valued manufactured goods are still produced in high income countries but require more capital investment and a more skilled labor force than can be provided elsewhere (as noted in Rodrik’s claim at the beginning of this posting.)

In the past couple of years, according to Rodrik, close to $300 billion have been committed to spending on manufacturing. He cites the example of the funds provided to Taiwan Semiconductor to build three fabrication plants in Arizon, projected to employ just 6,000 workers, which computes to a cost of more than $10 million per worker. Though semiconductor production may be a national and economic security priority, $10 million per worker seems an absurdly high cost of meeting such a priority. Complexities make it difficult to calculate the overall cost per worker of these subsidies to manufacturing entities; though whatever it is, it’s an expensive jobs program.

Rodrik concludes that to rebuild the middle class, generate a sufficient number of well-paid jobs, and reinvigorate those parts of the country that have declined or stagnated economically, an entirely different set of public policies will be needed.

In Behind The Curve: Can Manufacturing Still Provide Inclusive Growth?, to be published by the Peterson Institute for International Economics in August 2024, economist Robert Z. Lawrence, similar to Rodrik, argues that:

The industrial sector’s historic role as an engine of opportunity and inclusive growth is unsustainable. Government efforts to promote manufacturing to achieve goals such as industrial self-sufficiency, green transitions, and digital technologies, however well intentioned, may even make economic growth less inclusive. Instead, new policies are needed to help people, places, and countries cope with inevitable changes in the composition of employment.

Efforts to create sustainable, well paid, satisfying jobs will require new thinking. Throwing lots of resources at what worked in the past, especially given the challenges of climate change, not only won’t work this time but will make our transition to a more sustainable path to socio-economic well-being much more difficult.